Table of Contents

Open Table of Contents

NYPC Code Battle 2025

To cut to the chase, I participated in the NYPC Code Battle 2025 Finals and secured the silver award(3rd place). I’d like to share my experience and our team’s strategies for each of the problems/games.

NYPC Code Battle 2025 is a special programming competition hosted by Nexon, a major game company in South Korea. Their annual competitive programming contest, NYPC, has just reached its 10th anniversary, so they decided to host an extra competition(Code battle) this year. Code battle has a unique twist compared to other competitive programming contests: instead of solving traditional algorithmic problems, participants build an agent that is capable of playing the given 2-player game, and compete against other participants’ agents. However the usage of GPU was disallowed to prevent copy-pasting deep learning models, so the competition mostly revolved around traditional AI techniques such as minimax, alpha-beta pruning, Monte Carlo Tree Search(MCTS), and classic reinforcement learning.

Testing round - Apple Game

The game for the testing round was a twist on the famous Apple Game which went viral in korea a few months ago. Instead of being a single-player game, it was modified to be a 2-player game where both players compete to “claim more spots” in the grid by collecting apples within a rectangular subgrid that sums up to exactly 10. Each player would take their own turn to select such a rectangular subgrid if there were any valid such subgrids, and then claim all the spots in that subgrid. The game ends when neither player can make a valid move, and the player who has claimed more spots wins. Naturally re-claiming a taken spot is also allowed if you could choose a valid overlapping subgrid, so the game was quite interesting.

As you could probably imagine, the game tree was huge, so we implemented a basic alpha-beta pruning agent with a heuristic evaluation function that considered the number of remaining valid moves for both players. Since it was just a testing round, we didn’t put too much effort into optimizing the agent, but it was sufficient to help us warm up and perform well against the testing agent. I heavily doubt that our solution was actually somewhat competitive, but it gave us a good idea of what we should expect in the prelims/finals.

Preliminaries - Yacht Auction

Yacht Auction is another game with a twist based on the popular dice game Yacht(also known as Yahtzee). In Yacht Auction, the table rolls two sets of 5 dice each turn, and both players secretly bid on one of the two sets of dice. If their bid targets match, the higher bidder wins the dice set and the loser takes the other. Otherwise, both players take their own bid’s dice set. Note that if you lose a bid, you actually get a double refund on the amount you bid, which introduces another little twist into your bidding strategy. After each round, each of the players update their scores based on the standard Yacht scoring rules and openly share the results. The game continues for a total of 13 rounds, and at the end of the game, both players calculate their scores based on the standard Yacht scoring rules. There are a few other details, such as the first round not having a scoring phase so that each player maintains a dice hand of 10 dice throughout the game(which is revealed to each player), excluding the last round where both players must use all their remaining dice to bid.

The game has an overwhelming amount of properties that makes it quite difficult to design a strong agent. First of all, the game has a huge branching factor due to the secret bidding mechanism and the random dice roll, which makes it very difficult to use traditional minimax or alpha-beta pruning techniques. In hindsight, I’d imagine that most teams may have fell apart after realizing that their game tree search based solutions weren’t performing so well, as the amount of creative solutions you can come up with this game is kind of small in my opinion.

Another classic approach would be dynamic programming, given the probabilistic nature of the game and the fact that the game has a fixed number of rounds. Ideally it sounds great if you could somehow calculate the expected value of each possible move at each game state, such as what you would do in classic tabular Q-learning in reinforcement learning. However, the state space is quite daunting to use such table-based methods, which may have acted as another deterrent for most teams.

However, one of our team members(tlewpdus) quickly discovered that if you could just quantize the dimensions of the DP table just right, you could pre-calculate the ‘important parts’ of the table in advance(as the submission form allowed an extra 10MB binary data file along with the source code to be executed), and calculate the rest of the DP table on-the-fly during the game using some clever approximations. The quantization scheme is very important and the final performance of the agent heavily depends on your precision vs size tradeoff, so most of our efforts went into tuning hyperparameters to make the quantization better and using it better for our bidding strategy. I can’t exactly explain how we came up with the quantization scheme as it was mostly his work, but it borrows similar ideas from matrix factorization / low-rank approximation techniques.

To help us build on top of the base DP solution, we implemented a CI workflow on a private github repo that would automatically pit our agents against each other on every push, and log the results for us to analyze. This helped us a lot in tuning our hyperparameters and testing out new ideas quickly without having to manually run matches ourselves.

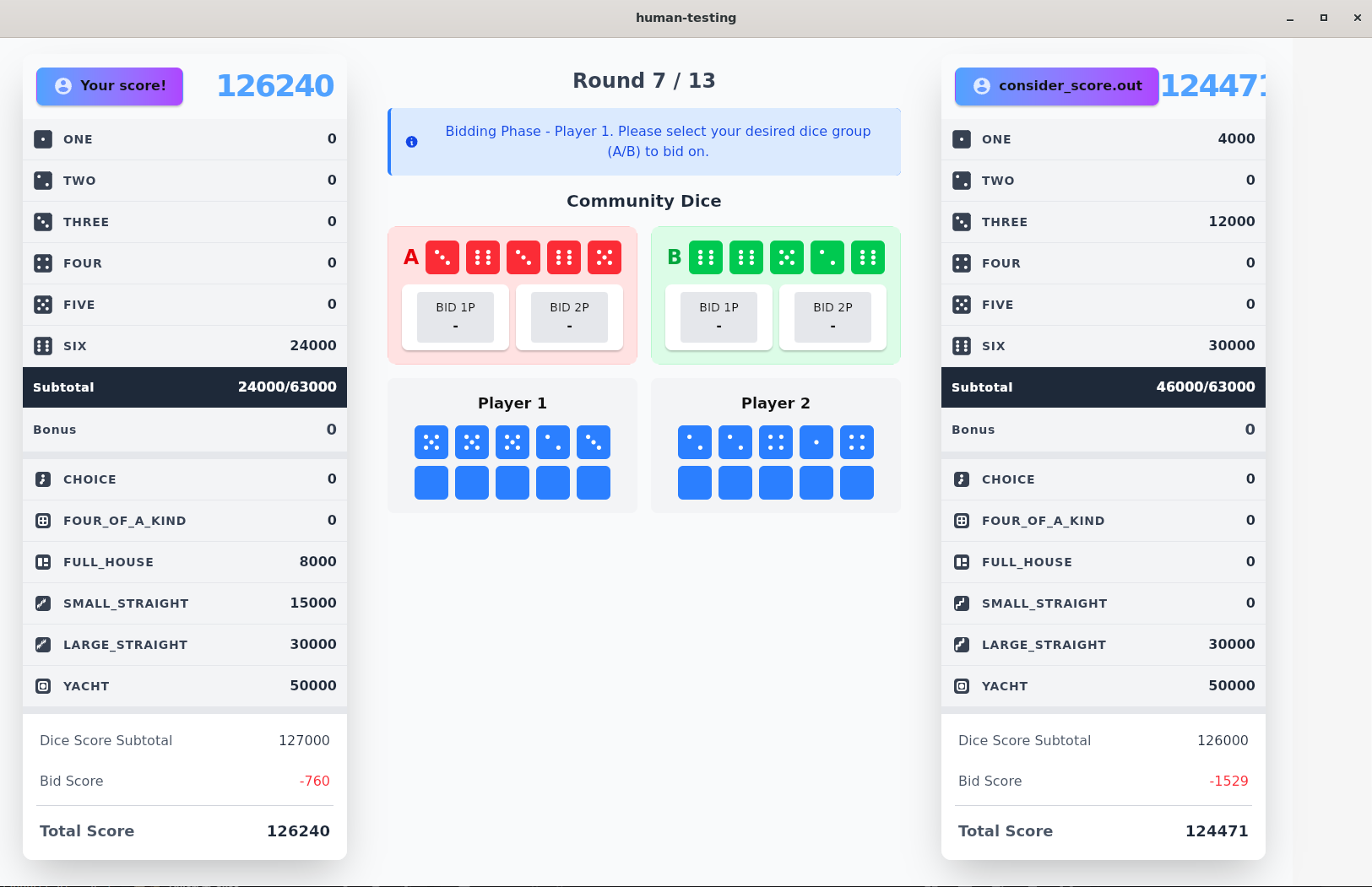

I also built a custom human testing tool(closed source for now since the code is embarassingly bad) to help us evaluate our agents by playing against it ourselves. It ended up taking too long to finish building it to the point where there was only about 2 ~ 3 days left until the preliminaries were over, so we didn’t really find much use out of it, but it was a fun learning experience nontheless as it was my first time working with Tauri + building a desktop app.

The solution worked! a bit too well even, as we managed to secure the top spot(~6th place) in the preliminaries. There were still some glaring outliers when we looked at our agent’s competition log with some teams performing absurdly well(probably the 1st / 2nd place teams), but we were quite satisfied with our performance nonetheless as we even managed to temporarily hold the 1st place spot for one of the rounds during the preliminaries.

I heavily doubt that there exists a win-against-all solution for this game given its complexity and adversary nature. One of our teammates(daniel604) kind of managed to come up with a mathematical proof that there does not exist a pure strategy Nash equilibrium for this game, which basically means that there is no perfect strategy that can guarantee a win against all possible opponents. This means that the game is heavily dependent on the opponent’s strategy, and you may have to adapt your strategy based on who you’re playing against. We kind of figured this out empirically as well while we were looking at some of our logs, figuring out that the detailed bidding scheme heavily matters when it comes to deciding the win or lose factor between two sufficiently sophisticated agents. Even our 1st place solution would internally lose against supposedly inferior agents due to some weird bidding interactions, which was quite frustrating.

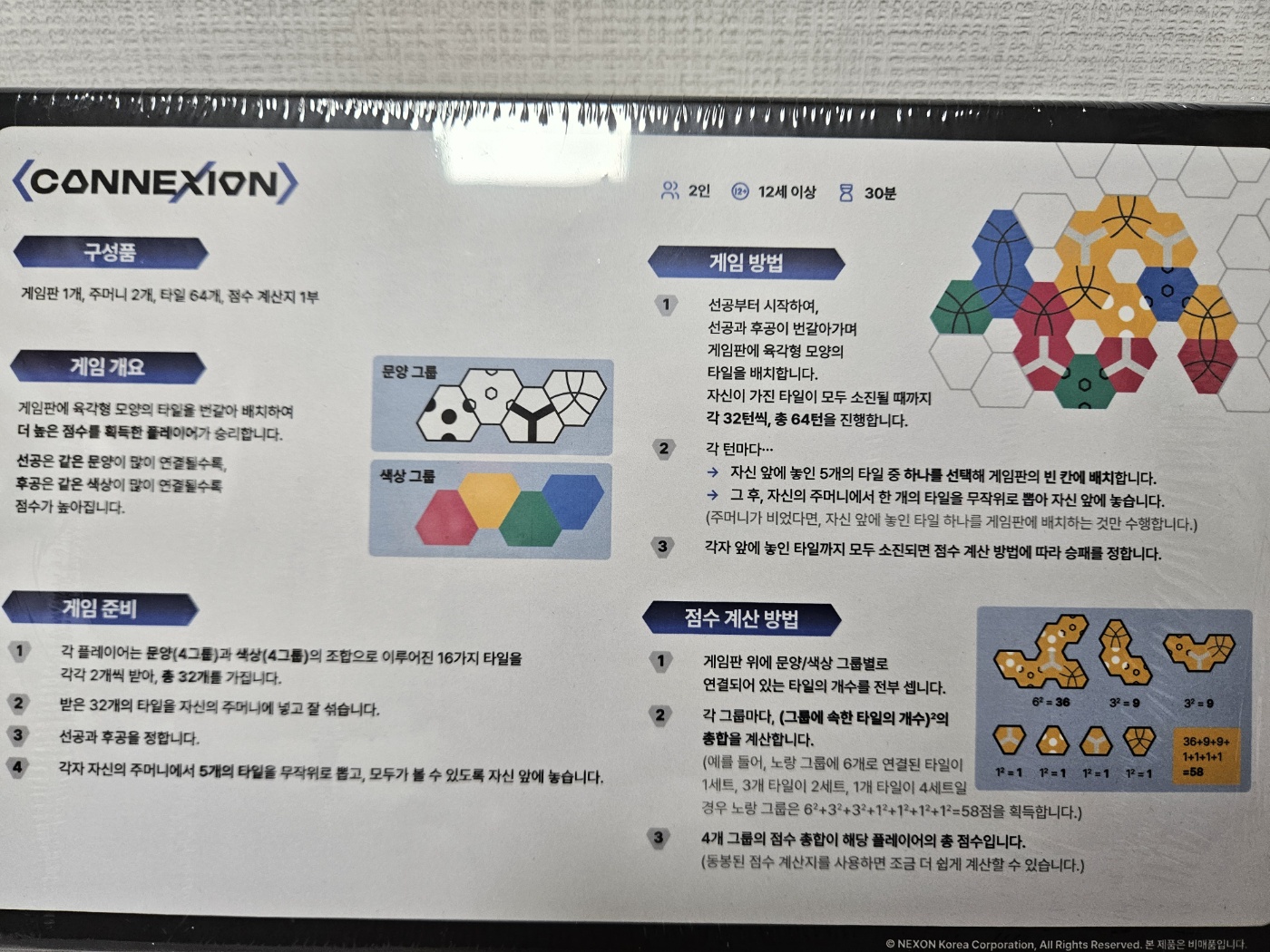

Finals - Connexion

Connexion is a two-player tabletop game that seems to have been custom-made for the finals by Nexon themselves. There is currently no available information about the game online from what I can find, so I’ll try to explain the rules as best as I can based on my own tabletop copy that I received from participating in the finals.

- Each player is given 2 copies of 16 unique tiles, each tile having one of four colors, and one of four shapes. That sums up to each player having 32 tiles, and the board consists of 64 tiles total.

- Players put their tiles in a blind bag, and will draw 1 tile from the bag each turn. Players each start with 5 random-drawn tiles in their open hand.

- Each turn, a player must place one tile from their hand onto the board, and then draw a new tile from the bag to replenish their hand.

- A tile can be placed onto any empty spot on the board, in order to maximize the player’s final score.

- The first player aims to maximize the number of adjacent tile connections that share the same shape, while the second player aims to maximize the number of adjacent tile connections that share the same color.

- The score is calculated at the end of the game by counting the number of “connected components” formed by the tiles placed on the board. A connected component is defined as a group of tiles that are adjacent to each other and share the same shape (for player 1) or color (for player 2). The score for each player is the sum of the squared sizes of their connected components.

From the game’s description, one can naturally infer that due to the squaring rule, having a large connected component is significantly more valuable than having multiple smaller components(If x + y = z, x^2 + y^2 < z^2). Furthermore, you could also strategize against your opponent by placing tiles that would block their potential connections, adding another layer of complexity to the game. The board itself is also quite intriguing as the shape is quite irregular, and you could tell that certain spots on the board are more valuable than others due to their potential connectivity.

Because we had used game tree search during the test round and DP/Q-Learning during the preliminaries, we expected the finals to require a new creative solution that would differ from these past approaches. The game definitely felt quite unique from our initial analysis, which led us to believe that there must be some sort of special property or observation we should exploit to build a strong agent.

The finals consisted of a non-stop 6 hour offline session in Nexon’s HQ building in Pangyo, South Korea. We were given a tabletop set of the game along with the instructions, and were allowed to discuss and implement our agents on-site. We were also given multiple “public rounds” to test our submitted agents against other teams’ agents which ran periodically until the end of the finals, and the first round started exactly 1 hour after the finals began.

1:00

After playing the game for ourselves for about 30~40 minutes, we were left absolutely clueless about our approach aside from just trying to implement a basic minimax agent with alpha-beta pruning. The game tree was still quite large, but we figured that with some clever optimizations and a decent heuristic evaluation function, we could at least build a somewhat competitive agent for the first public round. However we really did not want to start implementing it right away as our given time budget felt quite tight, and we were still in the belief that there must exist a unique property that could help us build a stronger agent.

However, we couldn’t just let the first rounds pass by meaninglessly, so we decided to split our team into two groups: one group would work on implementing the basic minimax agent, while the other group would continue brainstorming for potential unique properties of the game. Due to the tight time constraints, the finals allowed us to use any LLM service we wanted to generate code snippets or brainstorm ideas, so we heavily utilized Gemini 2.5 Pro and GPT-5 during this first minimax implementation phase to speed up our development process. Obviously, the LLM agent being available for use by the contest organizers also means that the organizers probably already checked that most LLMs aren’t near strong enough to solve the game by themselves, so we weren’t too worried about the game degrading into a vibe coding contest.

Our first solution was up about 1:20 into the finals, and we managed to score somewhere around the middle in the first few rounds. It was alright, but definitely not enough, so we were quite struggling to find a better approach.

3:00

Our brainstorming group came to the conclusion that there was no conclusion, and that we couldn’t just waste more time trying to find something that doesn’t exist. All of us started to all-in on the classic game tree searching approach, and we began to deviate into slightly different approaches. At this point, I was heavily regretting not having prior experience with other famous public projects utilizing fancy game solvers like AlphaZero or Stockfish, and was very suspective of a few other teams in the public round logs who seemed to perform a bit too well compared to most other teams. I was still tempted by the idea that there must be some unique solution that performs way better than others, so I decided to dive deeper into the stockfish docs and try to understand how their neural network based approach worked. It ended up being too much for me to digest and implement for the remaining hours, so I just settled for implementing a MCTS(Monte Carlo Tree Search) based agent inspired by the general idea of AlphaZero, but without any neural networks or deep learning involved.

However, MCTS in its purest sense without an evaluation function obviously took way too long to be able to perform well within the time constraints, so I had to come up with a decent heuristic evaluation function to help guide the MCTS search. After sharing my first solution, we converged onto the MCTS approach being our best baseline, and quickly figured out that this heuristic evlaluation was really important for the final performance of the agent. We were scoring around 10th place at this point, and wasn’t really sure if we could win a prize with our current pace.

6:00, Final Submission

After a very long and frustrating session of tuning hyperparameters, adding new hyperparameters, changing the evaluation scheme which basically felt like reward engineering in deep reinforcement learning, we were slowly improving our solution to be somewhere around 6~8th place each round. We still had a few random ideas to experiment around when it came to the 5 hour mark, but during our last hour, that one team which seemed to be leagues above the rest on the public round logs felt extremely weird to me. Based on the other teams’ performance, it was almost clear that all of us were doing the same Alpha-beta / Minimax / MCTS based approaches with slightly different heuristics, so how could one team be performing so dominantly better than the rest? Was there truly a unique solution that we all missed out on?

Right after the last testing round finished, when there was about 20 minutes left until the final submission, I decided to take a gamble and try to add in a new evaluation criterion that heavily prioritized the idea of ‘neighboring comopnents and bridges’, which was never used in our reward scheme before as we had ruled out to be quite useless compared to other reward criteria that focused more on direct rewards. However, this time I was able to discover that once the agent had a good enough baseline performance, using the bridges and neighboring components idea as a tiebreaker helped a ton in winning against other agents of similar performance levels. We quickly ran an internal test against our gathered solutions, and the results seemed to be a bit too good to be true. Our last submission which placed around 6~8th place was being absolutely dominated by this new solution, so we quickly decided to submit it as our final solution, despite not having it tested in any of the public rounds.

After a long agonizing wait, we were able to confirm that we secured the silver award in the finals(supposedly 3rd place), which was quite a satisfying result given our initial struggles with the game. At the ceremony, I was kind of disappointed at myself for not being able to secure at least the 2nd place as I was very confident with my last idea with our internal tests, regretting that I hadn’t tried it earlier. However in hindsight, I think I did the best I could given the time constraints and my prior experience, so I’m quite satisfied with the final result. It had been nagging me for a bit that I wasn’t able to contribute more to the preliminaries solution, but I think I was able to make up for it during the finals with my MCTS implementation and final evaluation idea.

Takeaways

Although I did try out reinforcement learning for my bachelors’ graduation project, this was the first time I had used a similar idea in a competition setting, and it turned out to be a happy surprise. I had dreaded the idea of having to fine-tune hyperparameters for hours in such competitions(like the ones on Kaggle), but thanks to the organizers we were given an interesting game setting that made the process quite fun and engaging. Just like the experience I had with MCC this spring, I’d love to participate in more competitions like this in the future that allow for more creative solutions beyond traditional algorithmic problem solving.